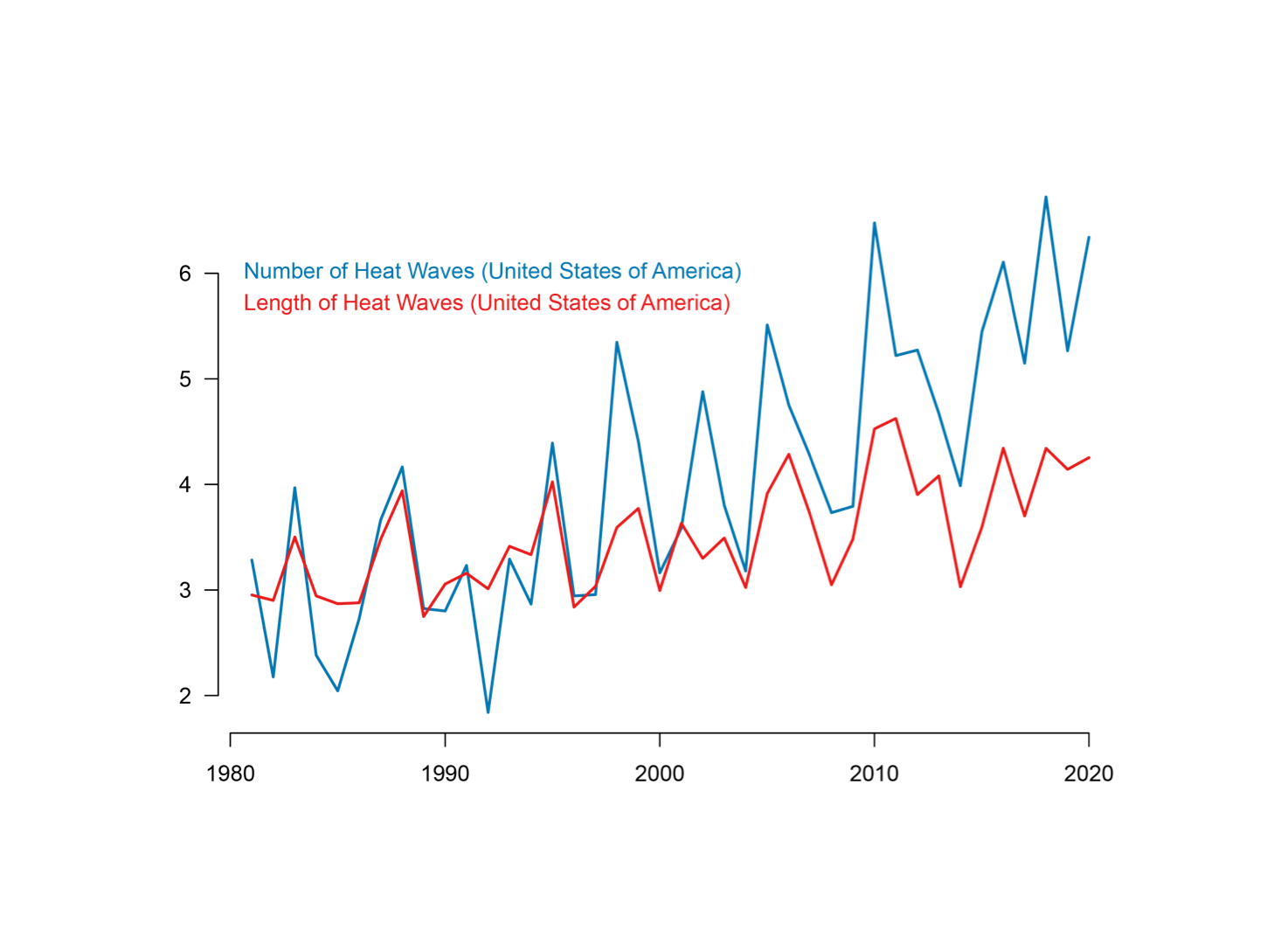

Americans are more likely to experience heat waves now than in the past

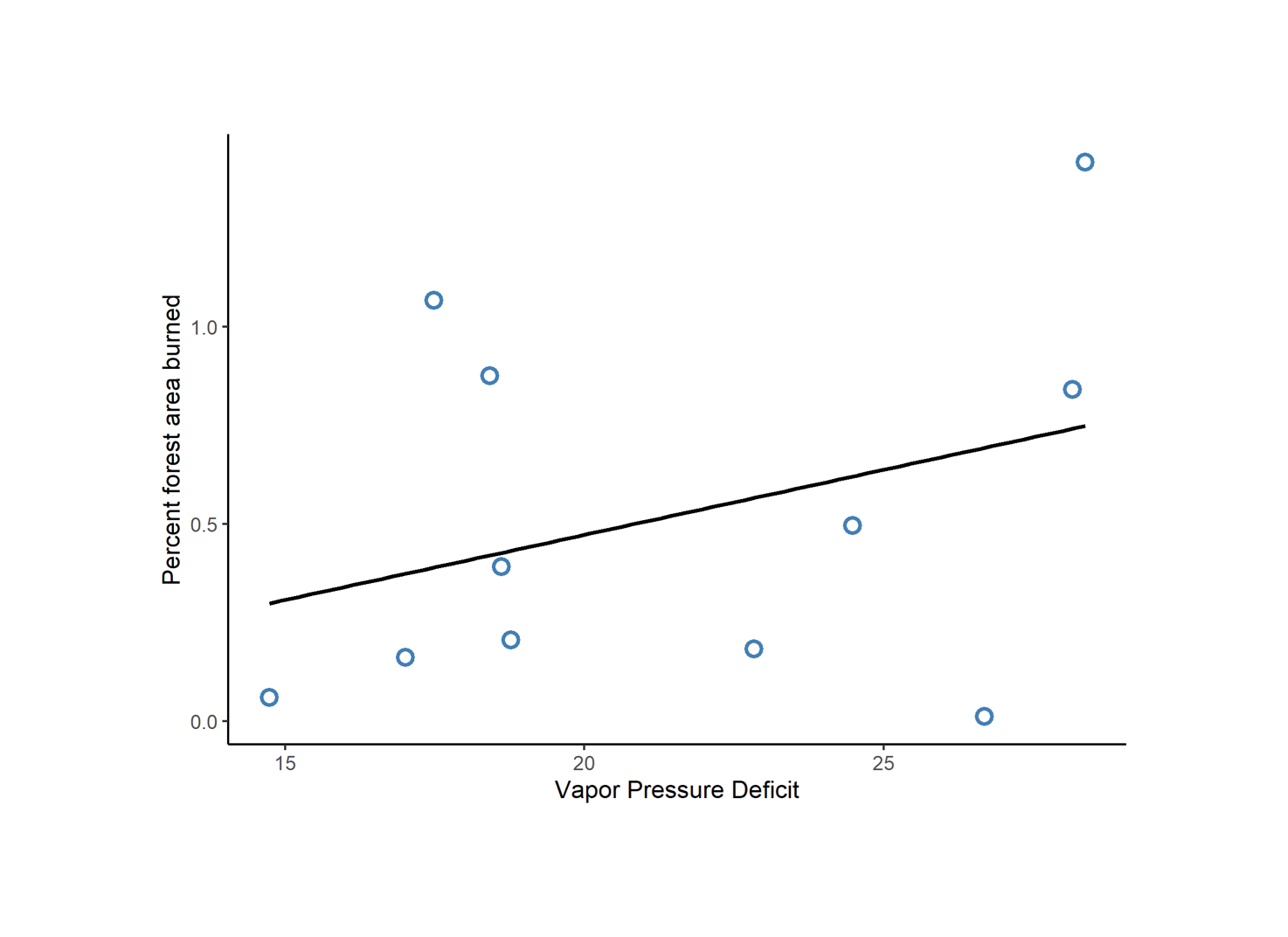

In the United States, exposure to extreme heat is on the rise. The average American went from experiencing three heat waves per year during the 1980s to five heat waves per year during the 2010s. Heat waves also have become more severe over time. In recent years, the average heat wave has lasted about four days—one day longer than the average heat wave in the 1980s. Heat waves are not just uncomfortable—they also can lead to lasting impacts on people and the economy. Numerous studies have linked extreme heat with illness and death among vulnerable populations, such as older adults, very young children, and those with chronic health conditions; harm to crops; increased risk of wildfires; and damage to essential services like transportation and energy systems.

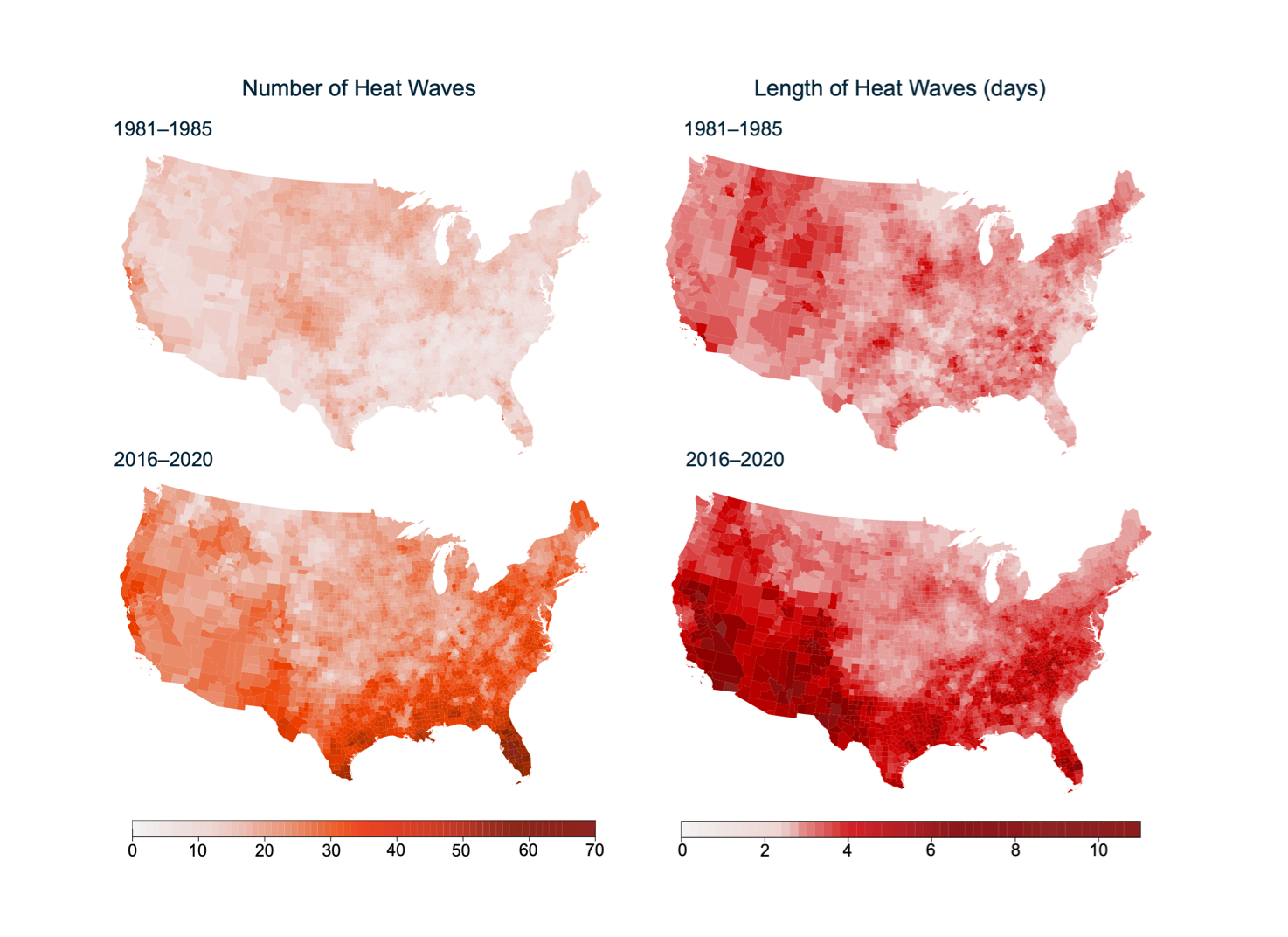

Heat waves are becoming more frequent and more intense

Almost all regions of the United States have experienced a significant increase in extreme heat exposure over the last several decades, but the trend is most concerning in the southern United States, where some counties are now experiencing more than 10 heat waves per year, on average. The average length of heat waves has increased the most in the southern and western United States and now exceeds five days in much of the country.

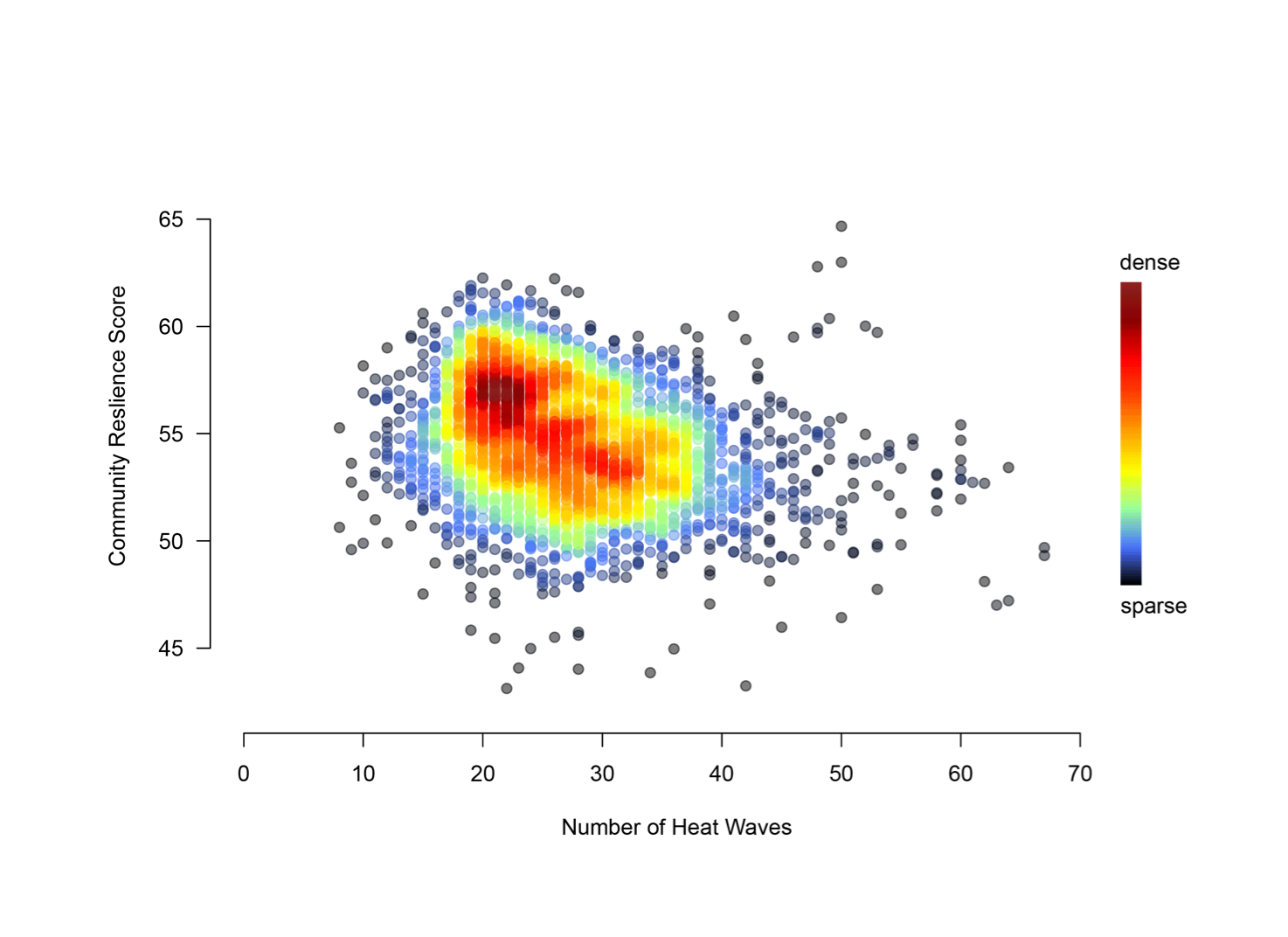

Heat waves are more severe for certain types of communities

Heat waves tend to disproportionately affect communities that are less prepared to mitigate the negative impacts. These data show the correlation between the number of heat waves in the most recent five-year period (2016–2020) and a measure of community-level resilience that’s available through the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s National Risk Index. We see a strong negative correlation between the number of heat waves and the community resilience score (both at the county level); in other words, communities with lower resilience tend to experience more heat waves. We could use the large catalog of county-level measures available on Google Data Commons to further explore which populations are disproportionally exposed to extreme heat. For example, you can view the association between heat wave exposure and median income here.